Kropserkel Inc. (Canada) and WSM Art Management (Germany) proudly present the official 2012 reincarnation of the world's most iconic symbol of science fiction in the history of film. This nameless robot is the 'Maschinenmensch' [human machine] or, the 'False Maria', 'Hel', 'Futura', 'Parody', and others.

With our interests deeply rooted in science fiction, armour, and the meaning of life, the opportunity to recreate the 1927 Maschinenmensch figure is a zenith level project for us. We felt that it was important to document some of the insights that were revealed to us throughout this endeavor. We hope to shed some light onto this enduring character whose true connotations are yet to be realized.

The Construction Process: Assets to a Resurrection

Instead of having to start on this project as a reverse engineering process, we were privileged to be working under the direct guidance of the Schulze-Mittendorff family throughout our project. This gave us unique access to rare information and production stills that provided invaluable and personal accounts of the techniques that Walter Schulze-Mittendorff used in 1925-26.

We recognized that this undertaking would be a memorable experience for us. We became bewitched by the original form, and its power to provoke introspection. Never before has an official replica of this costume been created. With the information we have amassed, we want our Maschinenmensch to reveal the stories that we have learned.

Our Replica Brigitte Helm

German actress, Brigitte Helm (1908-1996), was only 17 years old when she played the duel roles of Maria, and the false Maria robot in Metropolis. At the control of director Fritz Lang, she would also be the one to wear the Maschinenmensch costume in the film. She spent a rigorous and painful 9 days doing so in January of 1926.

As the basis for Schulze-Mittendorff's robot sculpture, a plaster cast of Helm's body was created from a mould taken of her while she was in a standing position. Her rigid body form would be required in order to fashion the armoured parts. Finding a versatile model to play this role for our 2010 recreation was an important task, and it wouldn't be long before a friend would introduce us to Cosette.

Cosette Derome, a Canadian actress and stunt woman was the consummate choice for the basis of our Maschinenmensch costume. She provided an excellent athletic body for our sculpture. As an actress, she could echo those unmistakable movements of the original figure as seen in Metropolis, and could still have the endurance to be able to perform with the restrictions of a full body armoured costume.

Capturing the Likeness of Synthetic Nobility

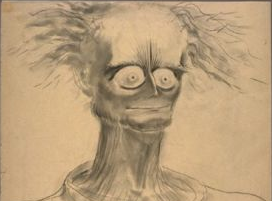

By far the most challenging and important part of our sculpture is the recreation of the facial expression. If we failed to hit this part, nothing else would matter. Depicted in our first generation casting below, we are on the path to bringing this iconic being back into existence for the 21st century to appreciate first hand.

Colouration

The original robot, only ever seen in black and white would need to be reborn into a world of colour. Working directly with Walter Schulze-Mittendorff's family allowed us to derive the original colouration details. Walter's notes indicated that a cello lacquer was used as a medium, mixed with silver aluminium / silver gilt, then shot through a spray gun onto the figure in order to produce the metallic appearance. In 1926 this was a very convincing simulation of metal surfaces, even on close inspection. The cello lacquer would have provided a glossy finish, and relatively clear, only showing an amber tint after multiple coats. The silver aluminium would have been in fine powder form purely as a pigment, and would have required the lacquer in order to adhere. Aluminium is a white metal, while silver-gilt is virtually indiscernible from gold when concentrated. Given that this was the mixture, we can derive that the finish must have been between these two metal hues, bringing us to the middle finish below.

The Eyes Have It

While the costume featured a uniform finish on all of its visible surfaces, photographic reference showed that the eye area appeared to receive additional colouration enhancement. The sclera (the white outer layer of the eyeball) was seen to be a striking gloss white. The raised irises featured a lighter metallic pigmentation than shown on the rest of the body. The eye lids appeared painted dark grey to further contrast the whites of the eyes just like eye liner make-up. These details brought out a necessary contrast to this region, drawing your attention here. This characterized the 'calm madness' expression that the script called for. Schulze-Mittendorff clearly had an excellent understanding of the importance of feeling as read through the eyes in his works.

The figure of 'Wrath' (left), by Schulze-Mittendorff, was one of the 'Death and the Seven Deadly Sins' costumes and sculptures used in Metropolis, and the concept sketch for the character of 'Dr. Mabuse' (right), both featured aspects that are characteristic of the Maschinenmensch. The pupil misalignment in the case of 'Wrath', and it's exaggerated and raised iris region in the case of 'Dr.Mabuse' are evident. So thoroughly consumed by their emotions, these characters can be regarded as seeing blindly.

Bertina Schulze-Mittendorff, daughter of Walter, provides her commentary on the expressions of the eyes captured in her father's works:

"This ‘calm madness’ is certainly caused by the eyes of 'Wrath' and 'Dr. Mabuse', but my father seems to be a master of causing effect by the look of eyes. In every eye pair one can sense a slightly different expression. Only Wrath’s eyes show pupils, all the other 7 figures don’t. This might be because anger, rage and fury are the most extroverted emotions; they each are cast out by the other. The eyes play an important role in this explosiveness.

In the eyes of the other deadly sins, including 'Death', you can sense a complete emptiness in the expression of the eyes. This underlines the purpose of those guises: they are masks of feelings which built up the unique character of what here is called 'sin'. They live only through their surface, inside they are empty in the sense of being not existent, without liveliness and substance.

This feels completely different in viewing the Maschinenmensch. Its stern look shows a hidden liveliness, there is a calmness inside which indicates that some higher spirit is dwelling there, a being with a much greater competence and consciousness as one is used to seeing in most real human faces. It looks enraptured but highly present. No madness penetrates through the eyes but only a silent awareness. Only its outside witness that death is the fate: it is a cold and rigid cocoon, a hull, a costume: transient. I would say the Maschinenmensch in its expression shows exactly the opposite of death and seven deadly sins and this difference is provoked even by the same artistic means. This is what art is about.

"

Body sculpture

Wikipedia describes 'Expressionism' as a cultural movement, initially in poetry and painting, which originated in Germany at the start of the 20th century. Its typical trait was to present the world under an utterly subjective perspective, distorting it to obtain an emotional effect and to vividly transmit personal moods and ideas. Expressionist artists sought to convey the meaning of "being alive" as an emotional experience rather than a physical reality.

At the height of this movement, Schulze-Mittendorff had the opportunity to bring an expressionistic piece to the world in the new media of film. It was an underestimated achievement. Like many things that have been so influential, and brought into being by humble individuals, with no delusions of grandeur, Walter modestly carried out this work. He simply did it. His work is proliferated in so many ways today. With frequent homages to his design in film, we realize how influencial his works have been.

The conceptualization of the first mechanical human being was a task befitting a visionary mind. In 1925, Walter may have been influenced by exciting and mystical world events, one being in 1922, when the archeological discovery of the Pharaoh Tutankhamun's tomb in Egypt was discovered.

The original Tutankhamun burial mask

The 'hemes' head dress, cobra peak, and beard forms culminate in an unmistakable similarity to the Maschinenmensch design. Like many of Schulze-Mittendorff's works, he has drawn inspiration from historical spiritual symbols and sculptural artefacts. The highly polished gold facial features of Tutankhamun's burial mask obviously struck a chord with him when he was asked by director Fritz Lang to imagine the appearance of a metal mechanical man.

What would an imitation woman look like if she were built by hand?

Schulze-Mittendorff indicated that he had no issues with coming up with a design. He asserted simply that "Expressionism was alive", and therein he had conjured his direction. With the design established, his priority turned to find a suitable material for its creation. At first he had considered using real metal in the form of an embossed copper sheet, but it was assessed that this would be too cumbersome and awkward to wear. A material that could simulate metal was sought, and while visiting an architectural model shop for another purpose, he found a small cardboard box that had been mailed to the shop labelled "Plastic Wood -sample without value", and as it was of no interest to them, the sample was placed at Walter's disposal. A working specimen of the material provided instant proof that this was to be the substance that would be used as the basis for the Maschinenmensch. This plastic wood turned out to be a pliable wooden material that was fast hardening on exposure to air. Once dried, it could be worked on and treated like naturally grown wood. Strips of muslin cloth were covered with this plastic wood and rolled out with a kitchen rolling pin to an approximately 2 millimeter thickness. The fibre reinforced material was then stretched over the plaster copy of Brigitte Helm's body form like a shoemaker would stretch leather over a buck form. When the material was dried and hardened the raw parts could be ground, and the contours cut into the armoured plates. The next step in the process was to provide technical aesthetics for the armour by assigning and fitting in surface details to enhance its appearance.

When the model forms were finished, the final stage was to paint the suit with a cello lacquer that had been mixed with "Silberbronze" (an alloy of copper and silver) and shot through a spray gun for a uniform coating. A polished " Weißmetall" (white metal alloy) appearance had been achieved that was very convincing even on close inspection. Fritz Lang's 'Metropolis' film was so ground breaking and grandios in scale, that it warranted efforts that would lead to a flawless looking production, and that would withstand the test of time, now very nearly 100 years later.

TO BE CONTINUED...

© 1997-2012 Kropserkel Inc. & WSM Art Management

Interest?

Contact us

|